Liberty Square, 70 years after liberation from the Nazis

Facts and pictures to compare what was 70 years ago and is now

Then and now photos of the Catholic Cathedral of the Virgin Mary showing the original location of the Jesuit College clock tower.

Then and now photos of the Catholic Cathedral of the Virgin Mary showing the original location of the Jesuit College clock tower.

During the Nazi occupation, German officers and soldiers loved to be photographed in the captured city of Minsk. They would have their pictures taken in front of wrecked vehicles, damaged Lenin statues, and destroyed houses. Minsk is abundantly represented in historical photographs – on the Internet alone can be found more than a thousand such images. Think of how many are kept offline in aging German family albums!

One of the main places that appears among the mountain of such odes to the occupied city is Liberty Square (Ploshchad Svobody). It’s been the focal point of amateur and professional photographers both on the ground and in the air. As part of a project commemorating the upcoming 70th Anniversary of the Liberation of Belarus, it seems appropriate to compare Liberty Square as it was 70 years ago, on the occasion of its liberation by , with what it is today.

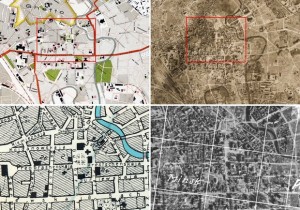

The German map shown here, in its upper left corner, was titled: “Plan der stadt Minsk,” or “Map of the city of Minsk.” It designated neighborhoods by planned ghetto numbers, and highlighted the main buildings and institutions. The red-framed area identifies the area shown in detail in the map on the lower left. The map itself was issued by the Luftwaffe General Staff after the start of 1941. The excerpted area is bounded today by Sverdlov, Nyamiha, and Yanka Kupala streets, and Independence Prospect to the south. In the center of the map sits Liberty Square.

In the upper right is shown an aerial photo taken by the Soviets on May 28, 1944, and the area marked in the red frame is essentially the same area depicted to the left. It’s amazing how much damage the Germans had left behind, with the city already five days occupied by Soviet troops. The extent of the destruction can be estimated from the photograph: the majority of buildings between modern Independence Prospect and International Street are bombed out with damaged roofs. But the areas adjacent to Liberty Square largely survived intact.

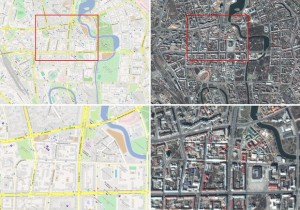

This is the same area in maps and satellite images today. Today, Kojdanowskaja Street has been renamed Revolution (Revalyutsyynaya) Street, Preobrashenskaja and Krestschenskaja streets have been renamed International (Internatsyyanalnaya) Street, and the stairs and river bridge that once existed on today’s Hyertsena Street are a distant memory. The Palace of the Republic on Kastrychniskaya Ploshcha (October Square) was once an indistinguished residential block behind the old Dominican Church of St. Thomas Aquinas, and across the city’s main prospect from the much older Aleksandrovskiy Garden.

One of the most important buildings on Liberty Square during the Nazi occupation was the “Generalkomissar für Weissruthenien” or General Commissariat for White Russia. It was housed in the former Basilian monastery until 1943, when the Germans completed the building that today houses the Presidential Administration.

Instead of the Nazi flag, today the banner that proudly flies on the building is that of the Federation of Trade Unions of Belarus.

The Commissariat then moved to its new location, and the Generalkomissar of White Russia, Wilhelm Kube, could walk to work from his home. He would soon after be assassinated that Sept. 22 as a result of the explosion of a bomb placed in his mattress by Soviet partisan Yelena Mazanik (she escaped Nazi-occupied Minsk to later tell the tale).

After the war, the former Basilian monastery became the House of Trade Unions, a function it continues to serve today.

Views from relatively close to the Catholic Cathedral of the Virgin Mary, both at the end of the Nazi occupation and today.

Toward the end of the occupation, a German photographer climbed one of the steeples of the Catholic Cathedral of the Virgin Mary to photograph the Generalkommisariat Building. Also visible in the earlier photo is the Dominican church of St. Thomas Aquinas and the House of Officers on the right. Today, the church steeples of the Virgin Mary Cathedral are set in the middle of a tight grid of buildings and it’s impossible to view the House of Trade Unions from the same vantage point (a nearby high spot near the old city hall was selected instead).

Remnants of the Dominican Church of St. Thomas Aquinas shown just after the war, and the same view toward the back of the Palace of the Republic as it is seen today.

The Aquinas church stood behind the Generalkommisariat/ Trade Union building and could have been restored to its original state, but in 1950, the decision was made to demolish the structure. The Academy of Music stands in its place today. The historic images shown here came from “Minsk Yesterday and Today,” compiled by V. Koledy (most photos were taken in 1945).

Corner of Lenin and International streets, first photo taken at the time of the Kube administration under the Nazis and the second photo taken today.

The corner of Lenin and International streets, a pleasant spot where people today enjoy benches, trees, and pleasant cascades of fountains, was before World War II the location of the old Hotel Europe, which held a department store on its first floor. Early in the war, the Hotel Europe was destroyed. In the photographs above, Anita Kube, second wife of Kommissar Wilhelm Kube, poses with one of Kube’s fellow German officers on an eerily serene day. Behind them stood ruins of the Hotel Europe, which was gradually cleared by Soviet prisoners of wars.

Instead of rebuilding the destroyed two-story governor’s house as it was before the war, a four-story box structure was put in place, which today houses the Academy of Music.

A new Hotel Europe was erected on the site of the former Municipal Theater, an area that even four years after the war remained in ruins. Quarters assigned to the pre-war governor of the Cathedral of the Virgin Mary were almost completely destroyed in the fighting that left much of the neighborhood completely changed.

Kiosks near the cathedral advertise (left to right) “Tickets,” “Reference Desk,” and “Newspaper Stand (Soyuzpechat)”.

In an odd contrast, kiosks located in the park somehow survived. In occupied Minsk, though, only a few stalls were situated in the neighborhood, including locations at the top of the hill leading down to Nyamiha Street, as well as across from the Catholic cathedral. Still, their ease of construction made them more likely to still be found after military action (even if the kiosk was actually a replacement).

Carl Zenner, a member of the Reichstag and former police chief of Aachen, was in office in Minsk as Chief of SS and Police from August 1941 to May 1942. He appears in the center of this photo in front of Minsk’s Cathedral of the Virgin Mary.

Kommisar General of Nazi-occupied White Russia Wilhelm Kube is shown in this photo meeting with the Chief of the SS and Police in Minsk, Carl Zenner sometime before Zenner’s removal to the Schutzstaffel (SS) main headquarters in Berlin. Zenner was apparently transferred on suspicion of inaction against the partisans fighting in the countryside, and reassigned back to Berlin. He later died in prison in Andernach, West Germany, in 1969 while serving a 15 year sentence passed down by a court in Koblenz for his part in carrying out Nazi atrocities.

Then and now photos of the Catholic Cathedral of the Virgin Mary showing the original location of the Jesuit College clock tower.

The Cathedral of the Virgin Mary is actually the last surviving vestige of an earlier Jesuit College that operated as early as the 16th century. After the 1863 January Uprising, Russian Imperial authorities ordered the closing of all Catholic churches in Minsk but the Jesuit organized church, which was made into a parish church earlier in the century. The clock tower and the college had long been in Minsk when the Nazis occupied the city.

Pro-Nazi demonstrators are shown carrying portraits of Hitler and pictures of Wehrmacht soldiers, while a sign reads in the foreground “Hefe-sirup fabrik,” meant apparently to represent a yeast and beer additive factory that operated in Minsk during the war.

Soon after the war, its ruins were demolished by the Soviets, finally obliterating this traditional Minsk religious landmark, which unfortunately proved to be a favorite rallying point for pro-Nazi demonstrators. Various rallies and marches, most of which were orchestrated by the authorities in an attempt to generate popular support for the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, were documented as having begun in front of the tower during Nazi occupation of Minsk.

Under the pro-independence white-red-white Belarusian flag, a large sign held up at a pro-Nazi demonstration in occupied Minsk read: “Only under the guidance of Adolf Hitler will Belarusians live in peace!”

Across the road from what was the former Jesuit College was an 18th century building that housed a pharmacy, post office, a boys’ religious school, an institution of Belarusian culture, and a cinema. During the occupation, the building was re-dedicated to the promotion of the “Volkdeutsche” community, or ethnic Germans who lived outside of Germany. The historic building survived the war and the years of Soviet neglect, only to collapse two years ago at the hands of Belarusian “professional restorers.”

The Gostiny Dvor on Liberty Square often served as a gathering spot for performances, meetings, and other official events, even under the Nazis.

The large Gostiny Dvor, the historical indoor market where traditionally merchants from other cities would come to sell their wares in Minsk, was also used in the Nazi occupation as a rally location. Here on May 1, 1943, people gathered under military supervision under a banner that read “Long live the unity of the people in the New Europe!” a reference to that part of the European continent dominated by the German Third Reich.

The Gostiny Dvor has repeatedly undergone renovations. The most recent was intended to restore the building to its original look, but, of course, a triangular glass dome was not part of the original Kramer-designed structure.

Designed and constructed by architect Fyodor Kramer in the 18th century, the Gostiny Dvor featured a comfortable courtyard until it was destroyed by bombs in the German invasion. The location also hosted a prominent execution. On Feb. 15, 1944, a day after he turned 28, Fritz Schmenkel, who voluntarily defected from the Wehrmacht near Smolensk and fought bravely with the partisans against the German occupation, was executed by the authorities with little more than four months before they would hastily evacuate the city.

Leave a comment