Museum Dacha of Vasil Bykov

Museum-dacha of Vasil Bykov will help you feel the ambiance of a house where a true artist lived

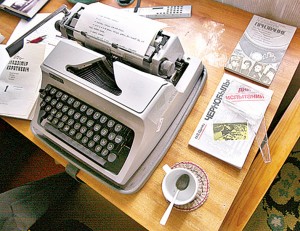

Vasyl Bykov's typewriter

Vasyl Bykov's typewriter

Vasil Bykov’s works Znak Biady (Sign of Trouble), Sotnikov and the Alpine Ballad are known worldwide. In 2014 the museum-dacha of Vasil Bykov was opened as a branch of the State Museum of the History of Belarusian Literature. At the present moment only 2 people constitute the staff of the museum: the head of the branch Ales Gribok-Gribovsky who’s at the same time a famous journalist and poet and Irina Chesnok, a junior research assistant who’s lately graduated from Belarusian State University.

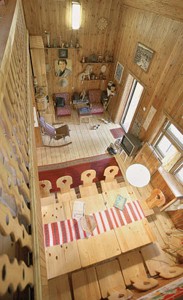

The museum leaves very pleasant impressions. Once you find house number 62 in Vinogradnaya Street you can feel at once the lively, cozy, special atmosphere that this house under birches emanates. When you come in you can’t get rid of the feeling that the host is about to come out to welcome you and right now is just busy drawing or writing in another room.

The first room we step in is penetrated with the sunlight. It’s decorated with a light wall paneling. Dining suite is made of glossy light-coloured wood. Under the table there is lamp with a round green lampshade. A small fireplace is decorated with brown tile. There are lots of souvenirs and paintings. The floor is glistening with fresh wood. You are to take your shoes off here. You’ve entered a house after all…

‘In 2012 Irina Mikhaylovna Bykova, the widow of the writer, appealed to the Ministry of Culture with a proposal to hand over this dacha to the government in order to turn it into a museum,’ says the head of the museum Ales Semenovich to start the excursion, ‘A letter to the president was written and the decision was taken at a high level. By the way Irina Mikhaylovna offered to choose either the dacha or the flat. Still we decided that it would be hard to make a museum in a condominium. On the contrary the dacha is a marvelous place. Of course we had to work on it. It took us half a year to complete the overhaul. In the last years Irina Mikhaylovna didn’t come here very often and the state of the dacha declined. The attic was destroyed. The floor got too damp. All this was restored. All the furniture and personal belongings were left unchanged.’

It’s curious that the writer himself participated in the process of projecting the house. It’s a known that he studied in Vitebsk College of Arts and kept his passion for drawing. He expressed his whole life in words as well as in pictures. On the first floor above the stairs you can find some of his sketches which actually are the chronicles of the construction of the dacha. There’s a basement on one of those, on another one from the October 26, 1984 there’s already a finished house with a column of smoke coming out of the pipe in the roof. In 1985 the Bykovs already celebrated New Year in this house together with Ales Adamovich’s family. The guests and the hosts are pictured wearing coats and hats while sitting at the fireplace: it should have been pretty cold in the living-room!

The dacha was built with a point to serve the classic as a quite place for creating. In reality Vasil Bykov spent little time writing here. He even left a note in his diary, ‘I didn’t feel like writing at my dacha. Everything was distracting me – neighbours’ discussions nearby, dogs barking, children playing around noisily…’

However Ales Gibok-Gibovsky is sure that he still spent some time creating there. In the Long Way Home Bykov recollects being busy on April 26, 1986, ‘I was at my dacha and instead of watering roses I was writing some article.’ On the whole though the family didn’t use to stay overnight there. Usually they would stay there from morning till evening. Moreover the building was cold while Vasil Vladimirovich liked to find himself in warmth.

In the living-room there are lots of paintings that were presented to Vasil Bykov by his friends. In the corner there is a record-player and a pile of old vinyl records. The one with Igor Luchenok’s songs even has a signature on the cover. Bykov liked to sit here in a rocking chair and listen to music.

Even though according to the writer’s diaries the dog barking occasionally distracted Vasyl Bykov from concentrating on his work, he still loved dogs. What is more they loved him too and never barked him up. Ales Gibok-Gobovsky consideres it to be a proof of what a kind and pure person he was. The documentary proof of that love can be seen on the walls of Bykov’s study. There’s a drawing called “All are here” that portrays his four-legged friends Naida, Rudka and Belchik running towards him.

The study creates a strong illusion of the writer’s presence. On the table there’s a draft of the story Golden Sand, a typewriter with a list of a manuscript tucked into it. On the right there’s a cup with a teaspoon… There’s a jacket hanging on the back of the chair.

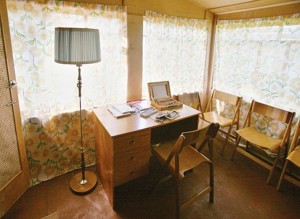

‘The purpose of the museum is to show the everyday life of a poet, a soviet intellectual of the middle of the 1980s,’ explains Ales Semenovich, ‘You see, everything is rather simple. That was Bykov’s lifestyle. Nothing superfluous. No pomposity, no luxury. Instead there are many books, magazines and paintings.’

On the bookshelves there are books with autographs. A really curious one was left by Vladimir Korotkevich on the first volume of his Selected Stories. It says, ‘To my dear friend Vasil Bykov whom I love not because “everyone” loves him now but because I loved him and supported him even when scolding him was considered good manners. And I will do so hereafter… and to his wife Irina, “one of the lads”. I wish them a kind, light, happy and prosperous life. Vl. Korotkevich. January 19, 1881. Kreschenie (the day of Jesus Crists’ christening – a holiday celebrated in orthodox countries – author’s note). ’

Also various diplomas are lined up here. They show the titles that the author was awarded during his life – Hero of Socialist Labour, Lenin’s award for the tale Znak Biady (Sign of Trouble) etc. You can unfold and hold any of them.

Vasil Bykov didn’t like pathos. Instead he had a sense of humour. Including self-irony. You can see this through the way he pictured himself in the sketches. For instance, the drawing Novice Gardeners that portrays two figures tottering along the road bent under the heaviness of their backpacks and bags (although the one who’s most bent is the husband). These are the Bykovs going to their dacha on foot. Perhaps the car has broken down or something…

The kitchen also caters for the hosts’ demands. It’s very tiny. They didn’t cook here a lot. Everything was preserved as it actually was. Regular cheap dishes, a thermos with Misha (the Olympic Bear), a teapot with a victory sign, plastic bread-basket… The only thing that catches your eyes is the painting in the upper side of the wall. It has watermelons, melons, grapes and other gifts of nature glittering on a white background. Of course it was all designed by the host. Although Bykov didn’t write here a lot he took pleasure in doing a lot of painting. His studio was set up in the attic above the garage. His friend writer Ganad Charkaziyan helped him with that.

‘ Vasil Bykov really liked his studio,’ claims Ales Semenovich, ‘ it was sunny and warm here in contrast to the cold house. He used to spend a lot of time here.’

The paintings made by Bykov hang together with those that were presented to him. A watercolour depicting a romantic castle was presented by Vladimir Korotkevich. On the backside there’s a line from Korotkevich’s poem Everything goes away but pride. Apparently after the death of his friend Bykov pasted here an obituary from a newspaper.

In front of the window there is an open sketchbook, brushes, tubes of paint. Over the sketchbook there is a drawing with a sign Artistic Rush. The writer drew a sketch of himself as a man who’s involved into the work at the easel. This drawing dates back to 1993.

In contrast to the archetypical image of a writer who’s unfamiliar with mechanisms, Bykov was one of those who could dissemble-assemble a car with his own hands. Automobile theme is also disclosed in his drawings: A Moment of Disgrace portrays the situation when apparently the author broke the traffic regulations. His frail figure is submissively bowing down in front of a militiaman. There’s a comment noting the date of the accident, ‘Crashed… March 29, 1991.’

The car isn’t in the garage yet. Although Bykov travelled a lot in his car. However there are instruments and auto repair handbooks. From the “riding” exhibits there’s a three wheeled bicycle that was once presented to Bykov’s wife.

‘ Vasily Vladimirovich’s neighbor remembered that on his way back to the city in a car Bykov would always drop by and ask if somebody needed to be given a lift,’ notes admiringly the junior research assistant Irina Chesnok, ‘ Can you imagine: a national writer, a classic…’

In the garage there’s an exposition Bykov’s Roads. On the map of the world the places that the writer visited are marked. Paris, Rome, Vladivostok, Stockholm, Helsinki, Madrid, New York, Cuba… In many of those his books were published. In a Ukranian village Velikaya Severinka that he once visited Bykov Museum has been opened today.

The maps drawn by the writer himself present another attraction. Those are the geographical ones of course…He drew them during all his life – that’s a habit ingrained in him from youth. A well-known case: in the beginning of the war the future classic lagged behind the troop and was caught by his own soldiers who after looking at his hand-made map took him for a spy. It was a miracle that he managed to avoid the shooting.

It is not an eventuality that there are birches growing at Bykov’s dacha. The author of The Alpine Ballad really liked these trees. When the dacha was being built one of the birches was hooked up by a crane. Afterwards Vasil Vladimirovich kept healing it for the whole month – he was looking after it and covered the wound with some substance.

During the construction works the birches were very small and Bykov was offered to cut them down as when they grow up they will disturb the view. He declined the offer. Today these birches are the landmarks of the museum. Some of them have grown so wide that you can’t even enfold them.

Moreover there are mushrooms growing right on the homestead. The terrace with the white tree trunks indeed disposes you to have a sit and think… Although the terrace still needs some repair. And the whole yard needs refinement. Then it will be appropriate for literary evenings.

‘We plan to hold conferences and literature evenings here,’ notes Irina Chesnok enthusiastically, ‘Right now there is no condition for this yet. The construction works are not fully finished. There is neither running water nor drainage system installed. The staff isn’t gathered yet. We urgently need a parking as well as road signs.’

Museum-dacha of Vasil Bykov is located not far from the village of Zsdanovichi. You can get there from the metro station Pushkinskaya by bus number 219, 419 or 420. Go as fas as the bus stop Internat veteranov Velikoy Otechestvenoy Voiny y truda ( The Internat of the Great Patriotic War and Labour Veterans). From there you’ll have to take a 1,2 km walk till the village of Zhdanovichi-6. It will take you around 15 minutes to reach the museum-dacha. The walk is going to be pleasant as you’ll be passing through a beautiful forest and suburbs.

The exact address is Vinogradnaya Street 62

Working days: Wednesday – Sunday from 11 am till 5 pm. At the moment the entrance fee is out of charge.

Text: by Ludmila Rublevskaya

Photo: by Alexandra Staduba and BelaPAN

Translated from Belkart’s Museum of Belarus website. This project is dedicated for popularisation of historical heritage of Belarus. Belkart is a national payment system of Belarus.

Translated from Belkart’s Museum of Belarus website. This project is dedicated for popularisation of historical heritage of Belarus. Belkart is a national payment system of Belarus.

Leave a comment